In writing about Paris restaurant openings, I'm accustomed to grousing about stillborn fads and failed trendhopping. (Meatballs, anyone? Wine by the litre?) But newly opened Place Sainte Marthe wine bar La Cave à Michel floors me, for it's perhaps the first place I've encountered since Bistro Bellet last fall that seems genuinely forward-thinking.

Located in what used to be the physical premises of online wine retailer La Contre-Etiquette, La Cave à Michel is a joint effort from two longtime neighbors - Fabrice Mansouri, formerly of La Contre-Etiquette, and Maxime and Romain Tischenko, the telegenic brothers behind nextdoor tasting menu restaurant Le Galopin.

Mansouri and the Tischenkos have transformed the awkward old Contre-Etiquette space into a spare, elegant, standing-room-only wine bar that offers, Wednesday through Sunday (!), a solid natural wine selection, a rousing atmosphere, and a winning menu of ambitious small plates produced from a comically small kitchen. The eponymous "Michel," as I understand the idiom, refers to a kind of Everyman figure, and this seems appropriate. Every neighborhood should have one of these.

La Cave à Michel's team will hopefully forgive me if I admit that nothing led me to expect such a grand slam from them. Fabrice Mansouri's work at La Contre-Etiquette was solid, but so low key as to be imperceptible to all but immediate neighbors. (I meant to write about La Contre-Etiquette for ages, and could never think of anything to say.)

Meanwhile, it took me two years to make it over to Le Galopin (full post forthcoming sometime), because I'd been put off by the brevity of the wine selection vis à vis the cost of the tasting menu. It fairly reeked of hype... And indeed when I finally dined at Le Galopin, I found it had more in common with Restaurant Pierre Sang Boyer than with, say, Bones; where the latter restaurant aims to impress fellow chefs, the former two restaurants seem to target the beginner-gourmand audience their respective chefs attained with TV exposure. A surefire indicator of this is the kitchen-sink dish, the plate that creaks beneath the weight of its component list, the better to impress novice diners who can't imagine how all those ingredients could be successfully combined.

At La Cave à Michel only once did such a dish arrive: a bit of mozzarella festooned with salmon roe, guindillas, dill, capers, etc. I still give Tischenko credit for using very good bufala and not the ubiquitous bad burrata we're currently wading through at apéro hour in this city.

Otherwise, the physical limitations of La Cave à Michel's kitchen seem to have had a tremendously beneficent influence on Tischenko's cuisine.

Almost every dish at La Cave à Michel is sufficiently spare for a diner to perceive the care taken with product. An oeuf mayo was amusingly do-it-yourself, with just a pot of mayo arriving with a gesture towards the bar's egg rack.

More involved dishes evinced admirable focus: a dashi-toned bar ceviche, a tartare bedecked in salty ricotta salata, or some daringly undercooked red shrimp, jelly-like and lividly fresh.

If La Cave à Michel presently has an Achilles' heel of sorts, it's that everything depends on Romain Tischenko's foxhole of a kitchen, and the bar's thronging demand means that plates can get forgotten or take inordinate lengths of time to arrive.

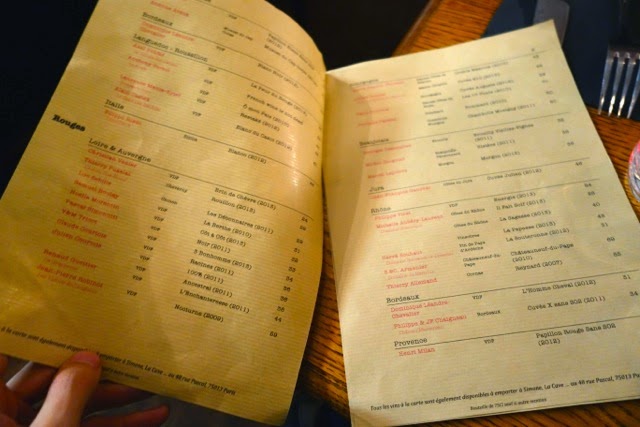

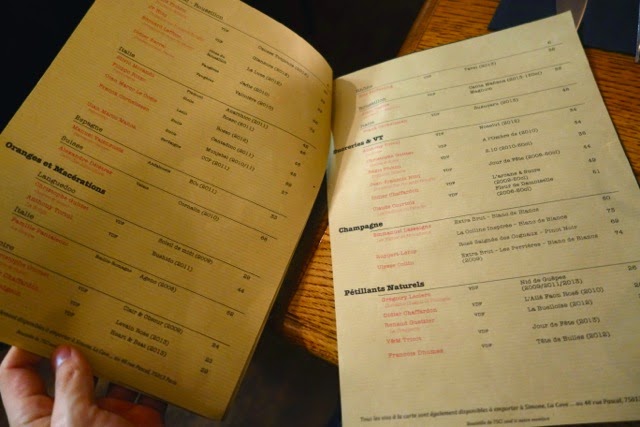

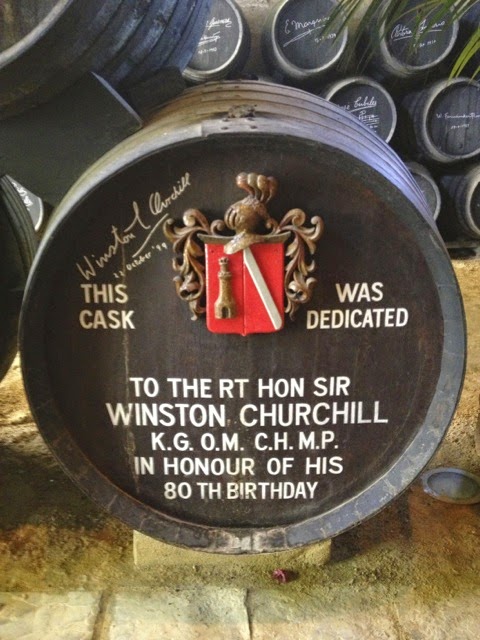

Happily, there's a lot to drink. Mansouri's long caviste experience is intermittently evident: the occasional back vintage curiosity enlivens a selection otherwise characterised by natural wine standbys like Henri Milan and Domaine Grange Aux Belles. It seems worth mentioning that Mansouri's choices at La Contre-Etiquette was less full-throttle natural than La Cave à Michel's, and all the more interesting for it. A prime example is the biodynamic and rather heavenly - but not exceptionally natural - 2010 Aligoté I enjoyed the other night, "Face au Lévant," by Dominique Lucas.

It's not the current vintage of this wine; it's something Mansouri bought in his Contre-Etiquette days. Sourced from 93 year old vines outside of Pommard, the wine was ruminative, smoky, and pure-toned, with a patient gravity rarely encountered in Aligoté.

The Native Companion and I polished off most of it waiting for a few forgotten dishes to arrive. To the bar's credit, I didn't mind at all. The ambience in La Cave à Michel on a lively Thursday evening is enjoyably reminiscent of an Andalusian bodega, only with fewer shrunken old men in caps, and rather more savvy young drinkers.

The Place Sainte Marthe has long possessed a secretive, out-of-the-way appeal, one undercut entirely by its two rather terrible terraced bistrots. Le Galopin, pricey and unspontaneous, never had a chance, on its own, to change the tenor of the neighborhood drinkers. La Cave à Michel, sophisticated, informal and inviting, almost certainly will.

La Cave à Michel

36 rue Sainte Marthe

75010 PARIS

Métro: Belleville

Tel: 01 42 45 94 47

Related Links:

Le Fooding's nonsensical, Google-translated note on La Cave à Michel, which incorrectly states that all the wines are sulfur-free.

A Time Out article on La Cave à Michel which is notable for the curiously open-handed way the author reveals his lack of wine knowledge. Odd for such a publication, which in my experience trades in the (imaginary) expertise of its local authors.